Since the beginning of 2020, the Hong Kong protests have focused on the “8 31 attacks” and the culture of outrage that is becoming a focal point of protesters. It did not help that police always reacts with overwhelming force and irritation to these “commemorations”.

What are the “8 31 attacks”?

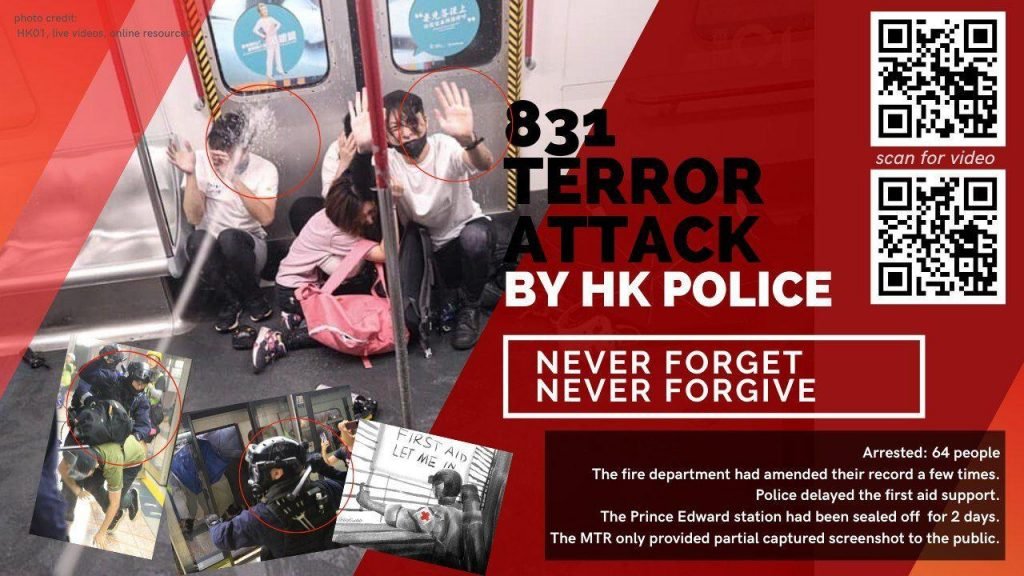

On August 31, 2019, a protest in the Mongkok area was violently dispersed by the police. Riot police entered the Prince Edward MTR station and beating up indiscriminately suspected protesters and passengers. After their intervention, the police locked down totally the station. A few injured persons were evacuated through Lai Chi Kok MTR station, further down on the Tsuen Wan line.

The incredible level of what appeared gratuitous violence by the police shocked the population. Some sights like a young man foaming at the mouth also caused people to believe there were casualties hidden by the police during these “8 31 attacks”. Obviously, no independent observer has been able to find any shred of evidence of any death happening at Prince Edward. Nevertheless, the refusal by the MTR corporation to release the CCTV tapes of that night fed into the protesters belief that people had died that night.

Soon, people started bringing flowers to exit B1 of the Prince Edward station as a sign of respect for the “dead”.

It so happened that exit was the closest to the Mongkok flower market, but also to the Mongkok police station. Thereafter those commemorations became part of the protester myth, and every month end lead to various degrees of confrontation with the police.

The culture of outrage

The protests have been largely fed at the start by a political awakening about the dangers of allowing China to implement officially what it was already doing covertly in Hong Kong.

But after summer 2019, there was a slip into a “culture of outrage” directed to the Hong Kong police. Heavy-handed tactics, abundant violence and name-calling such as “cockroaches” by policemen have fed a growing focus on the police as problem. This to a point that dangerously occludes the responsibility of China in the situation.

From demands that were focused on political ends (namely universal suffrage), the demands of the protesters progressively focused on police reform. About simultaneously, various pro-protesters propaganda channels began drumming the theme of the police as “murderers”, often misreading facts or amplifying things that fed into their narrative.

This created a “culture of outrage” that culminated in November, when online frontliner channels incited people to go and relieve the pressure on Polytechnic university frontliners. People called others to go and support students being “murdered”. The police showing up with AR-15 and other heavy weaponry did not help the general feeling. However, this hysteria caused a lot of arrests of people unprepared and not accustomed to street fighting.

The research of “martyrs”?

In fact, protesters have been hard pressed finding a proper “martyr” whose death who would mobilize masses. However, the death of the few martyrs that appear in their propaganda can never be ascribed uniquely to police. The very first of these was Marco Leung, the “yellow raincoat” man, who died after falling off from a scaffolding in Pacific Place, near Admiralty. Protesters used a yellow raincoat as a symbol of his “martyrdom” in subsequent marches. Police could however hardly be blamed in the matter as the fire department had been trying to assist the young man at the time of his fall.

After the “8 31 attacks”, the death of two young kids fed into the outrage. The most popular is Chan Yin Lam, a young girl whose body was found naked in the sea, but whose death was never investigated. Many protesters believed she was “murdered” by the police, although her linkage to the protests is tenuous at best.

A CCTV footage of the Hong Kong Design Institute showed her roaming aimlessly barefoot in the school, and apparently distraught. Trying to make eye contact with fellow students to whom she is all but invisible.

Her death would have certainly warranted an investigation, her body being found naked at sea. The police botched this one and the body was cremated in a haste before the outrage became public. And the defensive reactions of the police only fed into the belief they were covering up their crimes.

It is a bit paradoxical that a girl who was invisible to her peers while alive became a figurehead for the movement. Such was the dearth for an obvious “martyr”, and the girl had all the hallmarks of an ideal (absent) figurehead.

The second “martyr” was Alex Chow, a young man who fell in a parking building during a police intervention in Tseung Kwan O.

Protesters originally believed he was shot or disoriented by tear gas. Subsequent investigations proved that no tear gas was shot near the place Chow was when he fell. Neither was it proved that ambulances had not been delayed in assisting him.

Nothwithstanding this, the death of Chow brought out a huge outpouring of grief which would later find its expression in violent standoffs between police and frontliners during the “infinity war night” and PolyU.

Actual persons injured such as kids shot by the police seem to have attracted much less attention, let alone admiration. At the risk of being cynical, their fault was of not dying in the process.

A mutation in the movement

Still, as some observers noted, protesters have been marked by a negative tone and hopelessness. China gave no sign of budging on the demands of the protesters. At the same time, the risks protesters face when confronting the police are real. Beyond the injuries, the risks is also judicial. Over 7,000 protesters were arrested over the past months.

Originally, the fight was very much focused on democracy and human rights. Now, increasingly, the protests are turning to a darker side. Revenge of some kind is a key motive (often illustrated by the theme “never forgive, never forget”).

And the regular incidents every month keep awake the memory of police violence.

The pro-independence current has been gaining ground as protesters are now into a corner in terms of future with China. Chow and Chan unite now only a small fraction of the most dedicated protesters. The invisible “dead” of “8 31 attacks” seem to gather a stronger engagement of the population. As months went by, it became more difficult to maintain people died that fateful night of August 31.

A court recently ordered the MTR to release tapes of August 31 in Prince Edward station to a student for legal action. This student reviewed the tapes. Apparently, he never found material to substantiate the allegations of “deaths”. This sounded like the last nail in the coffin for the celebration of the “ghosts” of Prince Edward.

But on February 29 and March 31, protesters were still there with white flowers.

Police violence as unifying factor

Beyond the question of the “martyrs” and the political goals of protesters, what is obvious is that they are now moving away from the theme of “Chinazi” to move towards the police violence.

While police violence in Hong Kong is real, it is still is a much lower degree than in European countries. But happening in a civil city as Hong Kong which was not accustomed to this, it bruised minds and bodies. Today, however, this focus risks obfuscating the long term goal of obtaining democracy in Hong Kong.